Newspaper Interview – 6/15/1994

By BILL HALL – Staff writer WESTPORT

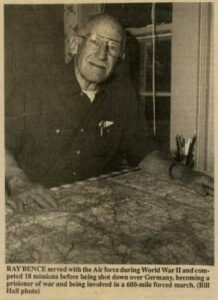

RAY BENCE served with the Air Force during World War II and completed 18 missions before being shot down over Germany, becoming a prisoner of war and being involved in a 600-mile forced march. (Bill Hall photo)

For individuals who may not have known much about World War II and watched the recent D-Day ceremonies, they might have concluded that the invasion ended the war. In fact, the war in Europe lasted 11 more grueling months with heavy losses on all sides.

Among those who saw all of this action following the invasion was current Westport resident Raymond Bence who flew 19 missions in a B24 against heavily fortified areas in France and Germany. Two months after his first mission his plane was shot down over Germany and he became a prisoner of war prior to being freed by the Russians at the close of the conflict.

This Sept. 27 will mark the 50th anniversary of his capture which came on the 19th mission over Bad Hersfeld.

He had come to the base of the 2nd Bomber Division of the 8th Air Force in Norwich, England by way of Westover Air Force Base. The then Sgt. Bence was in the nose turret of the 10 member B-24 when he flew his last mission on Sept. 27 heading for the Henschel plant in Kassel, Germany.

At that time, each crew flew 35 missions before it was allowed to go back home. This was his nineteenth mission and so far, all he had seen was flak and plenty of it but his first look at German fighter planes would be his last from the air.

“We had strayed off course by about 20 or 30 miles, ” said Mr. Bence. “We had dropped our bornb load off in some fields. I was later told we hit one cow.”

While they were returning, a wave of about 150 fighter planes including three groups of Messerschmitt 109’s attacked the 35 Liberators and within five to seven minutes the 2nd Bomb division had suffered its worse loss of the war.

“Only four planes got back to home base and three of them were so heavily damaged they could not fly again,” Mr. Bence said.

“It was the first time I had seen fighter planes,” he recalled, “up to that point we had seen a lot of flak and the German gunners were quite good. But up to that point we had never been in any real trouble.”

His plane was at about 20,000 feet when it was hit and within a few minutes, Mr. Bence was pulled from the turret by crew member Charlie McCann and they parachuted out.

“It was the first time I had parachuted,” he said. “At one point, I saw a German fighter coming at me. He just went right by. In the distance, I could see our plane go down.”

“There was light cloud cover below and once I went through that, I saw four or five ships (planes) burning on the ground,” he said. “I was heading to a field when a burst of wind took me into a tree. Some civilians rescued me from the tree and a couple of hunters came by and held me for the soldiers.”

Earlier in the war, bomber crews carried sidearms, however the military found that many of the airmen were being killed because they had guns. Because they were bombing in enemy territory, it was felt that if they were shot down, there was no use in trying to fight their way out of a jam and instead would submit to capture.

The crew members were spread out in the countryside and when Mr. Bence was captured, he was first taken for interrogation in Frankfurt where he was a cell mate of a British paratrooper captured in Arnheim.

“I have always wondered whether he was really a British paratrooper or not,” he said, noting that the Germans had been placing spies from various countries and mixed them with the military.

From Frankfurt, he was taken for a short time to another camp before being sent on to Pomerania in Poland where he was held from Oct. 7 of 1944 to Feb. 6 of 1945.

The camp had about 10,000 prisoners and except for the bad food, the prisoners were treated relatively well.

“Because we were enlisted men and officers we did not have to work,” Mr. Bcnce said, noting that they did regular cleaning but were not put into the labor camps. He added that the Red Cross provided parcels for the prisoners.

Many of the guards were older Germans. One who spoke very good English was found to be a man who had been a sewing machine salesman in Chicago prior to the war.

Two other soldiers were known as the “coal dust twins” because they provided coal to heat the barracks.

“There were a lot of roll calls, but the Germans could not count straight,” he said.

Meanwhile, the Adjutant had sent a message to Mr. Bence’s parents, Raymond and Bertha who lived in East Braintree. The message read in part “the Secretary of War desires me to express his deep regret that your son, Staff Sergeant Raymond 1. Bence, Jr., has been reported missing in action since 27 September over Germany.

“One of the first things you do once you are in a prisoner of war camp is try to find someone who was in your unit or from your Hometown,” Mr. Bence said. “I found out that a man from Braintree was in the hospital. He had been attacked by civilians when he landed and they broke both his legs and left him for dead. The German soldiers had to rescue him.

“Anyway, it turned out that he had a friend who lived across the street from my house Mr. Bence added. “He was about to be repatriated and so I had to get to him to give word to my parents that I was alright.”

“I sort of made a deal and went to the hospital and gave him the word. He got back to the states and gave the message that I was alright to my parents,” Mr. Bence added, noting they were told prior to Christmas of 1944.

On Feb. 6, the men in the camp were going to be moved because the Russian army had advanced to the south of the Stalag Luft IV camp in Poland. The soldiers were put on a forced march that would continue for the next two months and cover over 600 miles.

“We ended up on the first night sleeping in a field without any cover and having a sleet and snow storm,” he said.

Part way into the march, Mr. Bence took ill and that illness plagued him for the remainder of the march. The group was marched in areas along the Baltic Sea then south to an area beyond Berlin and then back to the east before finishing out in Annaburg.

“We were about seven miles northeast of Targau where the Russian and American soldiers first met,” Mr. Bcnce recalled. “By May 3, the Russians came to Annaburg and we were freed.”

Mr. Bence has only been on three flights over the last 50 years. “I don’t like to fly anymore,” said Mr. Bence. “The only three times I have been in a plane were all family emergencies.” Mr. Bence is planning at least one more plane ride later when he visits Germany for the first time since the war.